The Federal Open Market Committee has reduced its policy rate by a quarter of a percentage point, a move that is likely, though not guaranteed, to bring lower mortgage interest rates.

The Fed does not directly control mortgage rates, but movements in its short-term federal funds rate target often result in similar shifts in longer-term loan costs, including mortgages. That’s particularly true since, in October, the Fed stopped reducing its holdings of mortgage-backed securities, a policy called "quantitative tightening." This puts upward pressure on the rates banks charge on new mortgages.

Recent data has suggested weakness in labor markets, but consumers have continued to buy goods and services, and businesses are investing. If that resilience holds up, then the Fed’s action this week could be the last rate cut for the time being.

Market participants expect two more rate cuts in 2026, but the Fed’s famous “dot plot” suggested only one, and Fed Chairman Jerome Powell emphasized that the FOMC is still battling inflation. The dot plot shows where each member of the committee expects the federal funds rate to be at the end of the year for the next few years.

Further rate cuts are not guaranteed, especially if hiring does not slow dramatically and inflation remains stubbornly high. That means any decline in mortgage rates resulting from the Fed’s action may be small.

In fact, mortgage rates could even increase if inflation remains too high.

Survey suggests job market resilience

Data for September from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey suggests that even if there are signs of weakness in the labor market, they’re minor.

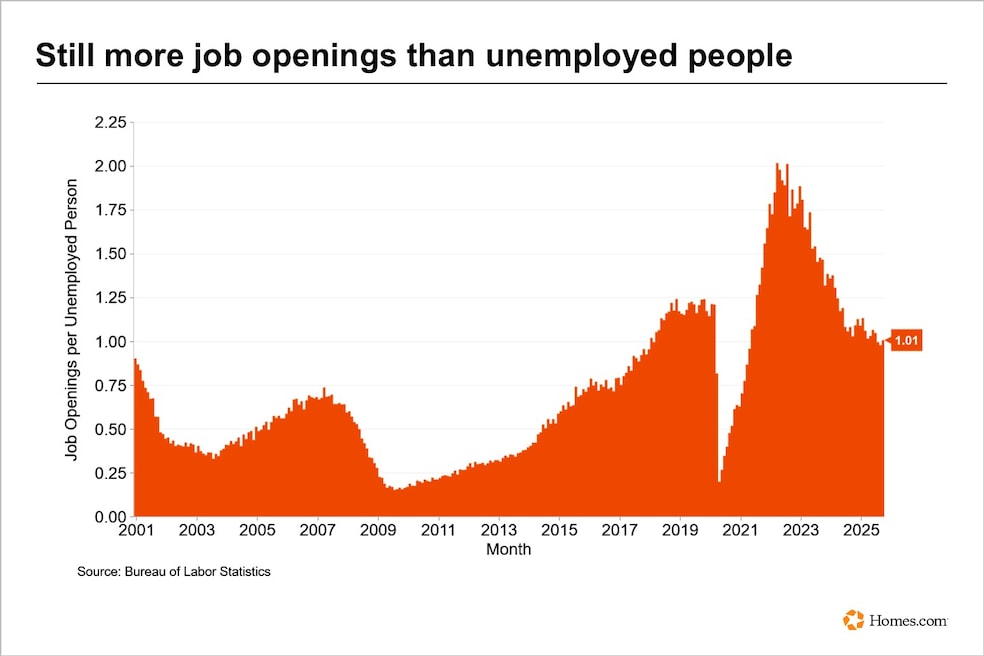

One measure of the health of the job market is the ratio of job openings to the number of unemployed persons — people who are actively looking for jobs but not finding them. Ordinarily there are more unemployed people than there are jobs listed, so the ratio is less than 1.0. Although the ratio has been declining since early 2022, the latest data still shows it slightly higher than 1.0, meaning there are more job openings than unemployed people.

That’s a sign of continued resilience in the job market — which, again, could mean fewer additional rate cuts going forward.

On the other hand, the JOLTS data also contained a widely watched indicator of weak job growth: the “quits rate” — the share of people who decided to leave their job — declined in September. This usually signals that workers aren't confident they could find another job if they quit.

Still, the current level of 1.8% is not terribly low, suggesting that even if workers are becoming more cautious about quitting their jobs, they’re not exactly clinging to them desperately.

If additional data released over the next month or so confirms that hiring is weak, then the FOMC would likely cut its policy rate again next year, particularly if inflation becomes less of a concern.

In short, however, whether interest rates — including both the Fed’s policy one and the mortgage costs that affect all prospective homebuyers — go up or down over the next year depends to a great extent on risks that are currently quite balanced.