In 1938, Ludd Spivey, president of Florida Southern College in Lakeland, Florida, sent a telegram to Frank Lloyd Wright. Spivey asked America’s most celebrated architect to help reimagine the rural campus into something that looked to the future.

Wright spent the next 20 years creating a new vision for Florida Southern, the work of which is now the bulk of the exhibit “Frank Lloyd Wright & the College of Tomorrow” on display at the AGB Museum of Art in downtown Lakeland.

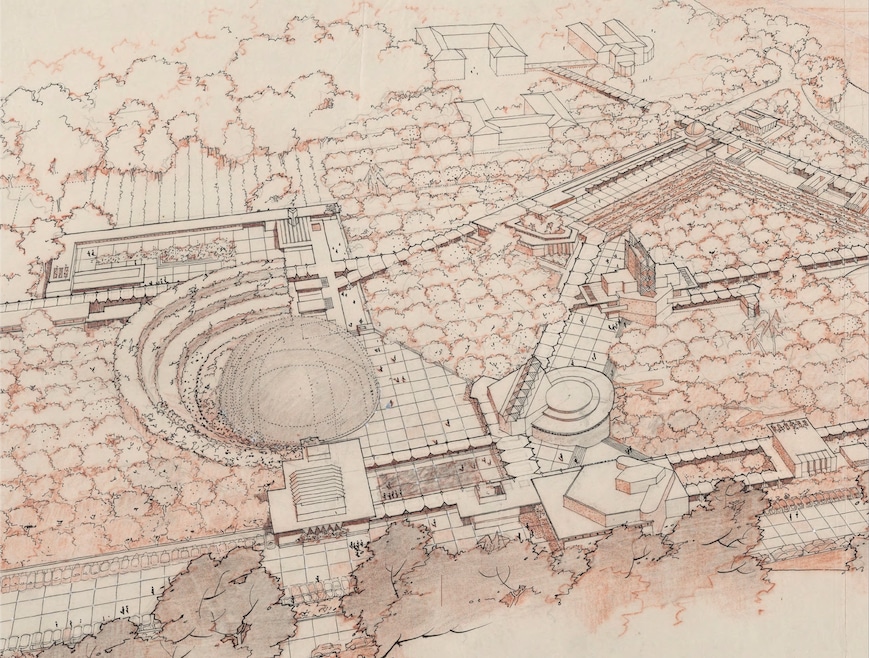

The 100-acre campus today comprises the largest collection of Wright’s buildings in the world. Twelve of his structures are situated throughout this former orange grove on the north bank of Lake Hollingsworth, including the only planetarium Wright ever designed, the Annie Pfeiffer Chapel, and the Polk Science building, connected by covered walkways called esplanades.

The exhibition includes two models. One shows the full extent of Wright’s plan for the school, including the elements that never came to be, such as the waterfront amphitheater and the swimming pool in the lake. The other model is of a faculty housing village that Wright had intended.

A second gallery room in the exhibit contains drawings of other Wright projects, where influences can be seen in Florida Southern. These include some of the best-known creations, such as alternate designs for the Guggenheim Museum in New York, Fallingwater in Pennsylvania, and the Ennis House in Los Angeles. Some of the images in the gallery have never been publicly exhibited before.

Jeff Baker, principal with Mesick Cohen Wilson Baker Architects, was one of the chief curators of the exhibit. He said working with original Wright sketches fulfilled boyhood dreams.

“I’ve been staring at many of those drawings in a book since I was about 14,” he said, “so to see those drawings live was very thrilling to me.”

Baker talked with Homes.com about how Wright saw the challenge of the campus, and the subtle ways his influence permeates modern-built America.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

By 1938, Wright was already one of the most prominent figures in architecture. What intrigued him about taking on the design of a college?

If you think about a college campus, it’s almost like a small village. This was actually his first opportunity to execute a project of this scale. At that point, he had been designing, at least in his mind, villages and towns. In fact, he wanted to redesign the whole country. He had designed a town called Broadacre City.

He was seeing what was happening with the automobile and how it was changing the patterns of life, so this was a way of exemplifying those principles that he had been espousing for about 10 years before this.

What were some of the factors with village building that he wanted to explore?

He had been probably more concerned than anyone of his stature about affordable housing. He had created back in the early 1920s what he called the textile block system, which is essentially (reproduceable) blocks for building houses.

Because they were working (on Florida Southern) toward the end of the Depression, a lot of students couldn’t afford to go to college at that time, so Wright and the president of the college worked out this thing where students could work three days a week on making these blocks and building the buildings.

It was not only about affordable housing but affordable architecture. Wright was an aesthete. He felt everyone deserved to have beautiful surroundings regardless of their income, so he was developing a way of putting architecture in reach of the public.

Florida Southern was his first chance to employ these thoughts over a large landscape.

Explain how Wright incorporated the orange groves that were on the site into the plan?

He wanted to connect people to the landscape. When he came to the site, it was filled with orange groves that were essentially on a grid system. All the trees had to be a certain distance apart.

He took the spacing of the trees and used it as a grid system on the site. All the columns on the esplanades were exactly half the distance between the trees apart. And he kept breaking that down to create his textile block. Each block is 3 feet long or four sections of 9 inches.

The grid system was part of creating architecture that’s easy for people to reach. If you poured a concrete slab and you put a grid on it, all you have to do is follow the grid.

So you see very few dimensions on his drawings.

He connected these buildings with these covered esplanades. And by doing that, he was able to control how people moved through the campus. He described the whole campus as a series of esplanades that occasionally became a building.

So there was a bit of a mystery involved that made it exciting for people. At least, that was the idea.

What did you want to showcase with the sketches of other projects in the second gallery?

I had to write captions for each of the works we were including. I realized as I was going through these drawings that many of them had ideas within them that were precursors to things that fully blossomed at Florida Southern.

There’s a very early drawing he did of an amusement park at [Wolf Lake, Indiana] that has this huge water basin. That’s exactly what he ended up designing at Florida Southern College, even though he never executed it. If you look at the renderings of the two, they’re probably 35 years apart, and yet you can imagine them being the same project.

You helped construct the Usonian House at the campus from his designs. What did you see in his designs for housing that revealed his thoughts on residential planning?

What’s important when people look at this thing is that this was designed in 1938. At the time in Lakeland, all the property lines were roughly 50 by 100 feet, and all the houses were just put in cheek-to-jowl all the way along the street.

He saw how open spaces could benefit people. So rather than having them crammed up in cities, he had them spread out along the countryside. This whole concept of freeing landscapes around the houses, this was something that wasn’t really thought of in American planning.

He was also the first person to develop houses with open floor plans. He was the first architect to recognize what the value of the car was. Before Frank Lloyd Wright, there were no carports.

Every time he built a house, he would say very freely that each of them was supposed to be considered a model of what American architecture could be, so he understood, and so did his clients, that there was a risk involved in doing this. This was a whole completely different way of thinking.

Now, we take these things for granted because the seeds that were in there have become commonplace in the planning of our homes.